1. Electronically fuel-injected engine with propeller drive

Electronically fuel-injected diesel engines have been and are being used in vehicles of many automobile manufacturers, as well as in medium- and high-speed engines on service vessels and specialized ships.

Over the past decade or so, electronically fuel-injected engines have begun to be used for two-stroke low-speed engines driving propellers and have increasingly proven their advantages over traditional engines. They utilize advancements in technologies such as angle sensors, rotation direction sensors, position sensors, distance sensors, pressure and temperature sensors, and level sensors to provide input and feedback signals for control and monitoring systems.

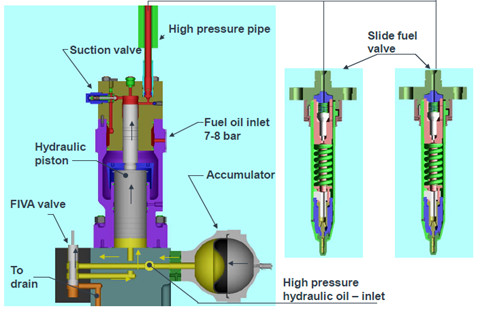

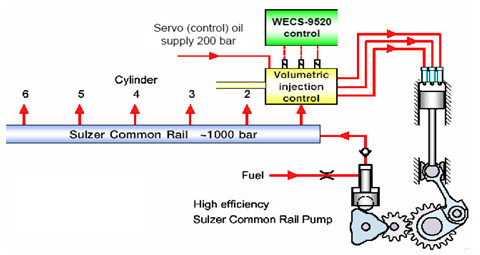

With four basic processes—fuel injection, valve control, starting control, and cylinder lubrication—“smart” engines, which use electro-electronic control and high-pressure hydraulic oil for power actuation, offer numerous advantages and the flexibility to meet the demands of the maritime transport market as well as the increasingly stringent pollution control standards set by the IMO.

Some advantages of electronically fuel-injected engines:

- While retaining the same structural components and principles as previous generations of engines.

- The fuel injection pressure is independent of engine speed, allowing the engine to operate stably at low loads.

- Fuel injection timing and valve operation can be easily adjusted.

- Optimizes lubricating oil consumption.

- Increases engine power (without using a large camshaft to drive the high-pressure pump or exhaust valves as before).

- Operators find it convenient to monitor, adjust, and assess the engine’s technical condition.

- Reduces maintenance costs and labor (with increased TBO—Time Between Overhauls).

- On the other hand, smart engines require operators to be updated with new knowledge, possess a basic understanding of sensor technology and electronic control, and be familiar with methods for inspecting, diagnosing, and replacing electro-electronic equipment when necessary. They must also have the skills to handle situations involving newly operated equipment such as high-pressure pumps, exhaust valves, hydraulic pumps, and control valves.

The most common smart engine series currently on the market and installed on newly built vessels are led by the MAN B\&W ME-B/C engines, followed by the RT-Flex series from WinGD (formerly Sulzer), and the Mitsui–Eco series from Mitsubishi.

2. Gas-Fueled Engines

With stricter requirements and the goal of minimizing air pollution by 2050, liquefied gas fuel has become a leading alternative to conventional liquid fuels in the maritime transport sector.

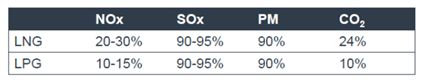

The pollution reduction potential of liquefied gas fuels, including LNG and LPG, is significantly higher compared to traditional liquid fuels:

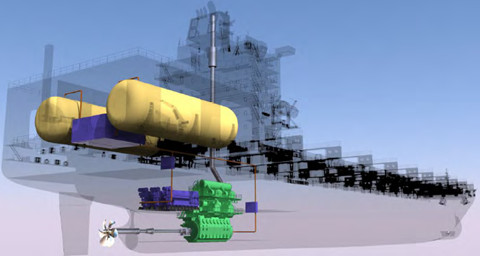

The first ships with gas-fueled propulsion systems have already been built and continue to be constructed at shipyards. News outlets have reported on the newly built 23,000 TEU container vessels—400 meters long and 61 meters wide—such as the “CMA CGM Jacques Saade,” delivered in September 2020, followed by the second vessel in late October 2020 for CMA-CGM. These ships are powered by the WinGD 12X92DF engine, with a design output of 63,840 kW at 80 rpm. This stands as clear evidence that propulsion engine technology has entered a new phase, with ultra-large, two-stroke, straight-scavenged engines operating on gas fuel.

It is worth noting that the entire propulsion system, including the main propulsion engine and generator engines, runs on gas fuel. The liquefied gas currently used as fuel on ships is Methanol; however, several other liquefied gases, such as Ethanol and Ammonia, are highly likely to become marine fuels in the near future.

Manufacturers offering these new designs include MAN B\&W with its ME-GI series, developed from the earlier ME engines. The detailed designation may vary slightly depending on the type of fuel used—for example, the 6G50 ME-C9.5-LGIM (Liquid Gas Injection Methanol) engine.

In addition, WinGD competes in this market with its X-DF (dual-fuel) engine series. These engines fully adopt the principles of low-speed, two-stroke, straight-scavenged engines and can operate on both types of fuel (dual fuel).

When liquefied gas fuels such as Methanol are used, many questions arise and have gradually been answered:

- Fuel supply sources and market as well as national availability.

- Safety and fire/explosion prevention requirements.

- Onboard storage space and design requirements.

- The process of switching between gas fuel and liquid fuel.

- The feasibility of retrofitting existing engines.

- Fuel cost compared to conventional fuels.

3. Alternative Fuels

With the IMO’s goal for 2050 and vision toward 2100 to reduce greenhouse gas (CO₂) emissions, clean fuels are being researched, and several promising options may become a reality in the near future. Some have already been used in certain vehicles, such as Audi’s e-gasoline fuel.

Currently, liquefied natural gas (LNG) is being used and is expected to remain a dominant trend in the coming decades, alongside technologies for capturing LNG from biogenic sources (bio-LNG). However, LNG is not yet a comprehensive solution for pollution reduction, as CO₂ emissions are only reduced by about 15–20% compared to traditional fuels. Electric fuel is increasingly seen as a promising option to meet these environmental requirements.

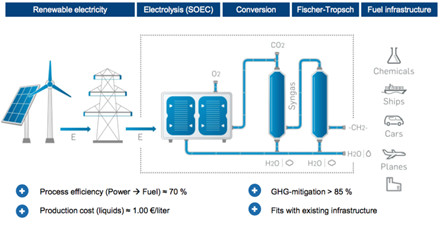

Electric fuel (e-fuel) is an alternative fuel recently studied and expected to be a superior solution for reducing greenhouse gas emissions, especially CO₂, with a vision toward 2100. It is produced by storing electrical energy from renewable sources (such as wind and solar power) within the chemical bonds of liquid or gaseous fuels. This process allows for the creation of various types of e-fuels, depending on the fuel type synthesized—for example, e-gasoline, e-diesel, e-LNG, and so on. In other words, e-fuels are similar to traditional fuels (LNG, diesel, gasoline, etc.) but are not derived from fossil energy sources; instead, they are produced through synthetic processes.

Essentially, through chemical processes, electrolysis (using electricity from renewable sources like solar and wind) separates hydrogen gas from water. This hydrogen is then fed into catalytic reactors along with CO₂ gas (which is captured or sourced from emissions or other origins) to produce hydrocarbons—the main components of fuels such as methanol, diesel, and LNG.

However, many questions arise regarding e-fuels:

Where does the electricity used in the electrolysis process come from? If it is sourced from clean energy like solar or wind, it is entirely feasible. However, currently, the contribution of these energy sources remains very limited. If the electricity comes from fossil fuel power plants (coal, oil, natural gas), then it’s no different from before, as a significant amount of greenhouse gases would still be emitted into the environment.

What about the product cost? Due to the complex processing involved, the price reaching consumers is quite high. It is hoped that technological advancements and wider adoption in production will help reduce the cost of e-fuels.

Infrastructure readiness? Essentially, e-fuels are no different from the fuels currently in use, except they are produced synthetically rather than derived from fossil sources. Therefore, storage, transfer, and supply systems require no changes. Likewise, engines and vehicles do not need to be modified or redesigned compared to current designs.

4. Some Other Important Technological Changes

Variable frequency drive technology

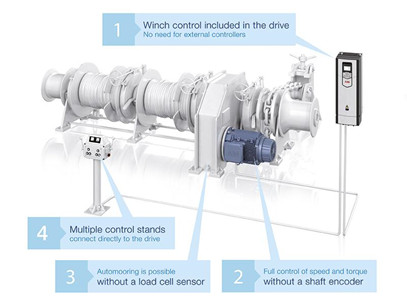

Motor speed control using variable frequency drives (VFDs) or frequency converters is applied in various systems such as winch and anchor speed control, cooling water temperature regulation, fuel oil temperature control, and more.

Ballast water treatment technology and equipment

As the D2 ballast water management standard gradually becomes mandatory for vessels, ballast water treatment systems are becoming familiar to seafarers. These systems use UV radiation, electrolysis, or chemical methods for disinfection, combined with filtration to clean ballast water. Many manufacturers offer such equipment on the market, including domestic producers in Vietnam with local brands.

Engine exhaust gas treatment technology

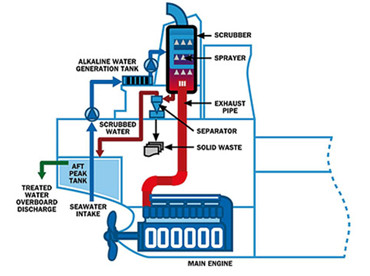

With stricter SOx emission control standards for ships effective from 2020, shipowners have two options. One is to switch to using Very Low Sulfur Fuel Oil (VLSFO) containing less than 0.5% sulfur. The other is to continue using high-sulfur fuels but treat exhaust gases with a scrubber system. Scrubbers are mostly installed on large Capesize bulk carriers with long operational routes and high fuel consumption per voyage. Compared to the VLSFO option, ships using scrubbers represent only a small fraction of the fleet. There are two types of scrubbers in use: open-loop systems that use seawater and discharge directly overboard, and closed-loop systems that use freshwater.

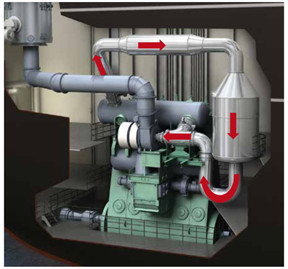

Another device used to meet NOx emission reduction requirements under the Tier III standard, applicable in NECA (NOx Emission Control Areas), is the Selective Catalytic Reduction (SCR) system. Newly built ships currently only meet Tier II standards and cannot achieve Tier III compliance without appropriate exhaust gas treatment, design solutions, or suitable fuel types. The SCR system is currently the solution to satisfy Tier III requirements. SCR is a reaction chamber installed along the exhaust gas flow path, either before the turbine (High-Pressure SCR, HPSCR) or after the turbine (Low-Pressure SCR, LPSCR). Inside, NOx is neutralized through a catalytic reaction using a reductant such as urea or ammonia (NH₃).

Internet and smart devices

Touchscreens are now very familiar on smartphones. Similarly, on ships, control and display screens for various systems and equipment are being modernized to use touchscreen technology, allowing easy operation and data extraction.

Today, Internet access is no longer unfamiliar to ships operating across the world’s oceans. Consequently, requirements for cybersecurity have become mandatory. Seafarers can use the Internet to stay connected 24/7, allowing ship operation data and technical equipment data to be continuously monitored online from shore. In some cases, remote control from shore stations is possible, making communication, technical support, and assistance faster and more convenient.